One of the most popular sections in Everyone Loves You When You’re Dead was the chapter in which the 50’s r-and-b singer Ernie K-Doe tried to arrest me after I interviewed him for The New York Times.

The reason I went to visit Ernie K-Doe in the first place was because of a writer and drummer named Ben Sandmel, who is the go-to-guy in New Orleans for local musical color. And Sandmel, who first brought me to the Mother-in-law Lounge and introduced me to K-Doe, has after many years finished an extraordinary book on the life and times of the never-dull Ernie K-Doe. (I still listen to the tape recording Sandmel gave me of one of K-Doe’s radio shows, in which he offers to give away diamonds to get people to come to his concert.)

Sandmel was kind enough to share with us an excerpt from his aforementioned book Ernie K-Doe: The R&B Emperor of New Orleans. And it provides another perspective on the incident from ELYWYD…

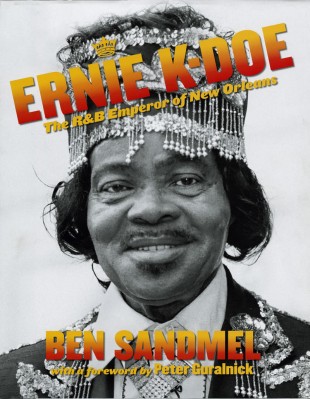

Ernie K Doe Book Cover

“I don’t need your little paper!”

Such withering scorn is rarely directed at the New York Times. It’s an impolitic outburst for an aging rhythm and blues singer who yearns to jump-start his career—especially if he shouts it at an admiring Times critic just after an interview. Particularly if his harsh words accompany harsher actions: halting a song midverse to accuse the critic of secretly taping his performance. Demanding the surrender of the critic’s microcassette machine. Calling 911 to report a robbery in progress. Locking everyone inside his tiny nightclub so that patrons and critic become a truly captive audience. Instructing a burly employee to execute kung fu moves by the door to discourage thoughts of escape.

But a veteran New Orleans rhythm and blues singer named Ernie K-Doe committed all these major breaches of professionalism. It went down at the Mother-in-Law Lounge, K-Doe’s self-adoring shrine to his big hit from 1961. When cops arrived with guns drawn–ready to quash an armed robbery but powerless to stop an alleged theft of intellectual property—the critic, Neil Strauss, explained that he’d come to the lounge to write an article that would “let more people know about Mr. K-Doe.” But Mr. K-Doe didn’t perceive Strauss’s visit as a rare chance for high-profile coverage, because Mr. K-Doe had barely heard of Strauss’s employer. There was no reason why K-Doe would—or should—have been familiar with the New York Times. Virtually none of “all the news that’s fit to print” has relevance in New Orleans’s music community, where the cell-phone grapevine prevails. K-Doe’s accusation of aural thievery didn’t come completely from left field, either. There is a niche market for live albums, especially overseas, where an odd concept of authenticity often favors low-fidelity recordings.

The police eventually settled matters, the hostages were all set free, and Strauss was released with the tools of his trade intact. So was Times photographer Ebet Roberts, whose cameras K-Doe had tried to confiscate. Both felt stunned by the dispute, which was quite unprecedented in their professional experience. Even so, in a classic case of lemons-to-lemonade, the despised “little paper” gave Ernie K-Doe a half page of favorable, bemused coverage, accompanied by a flattering photo. On May 17, 2000, under the wry headline the mother-in-law of all visits, Strauss generously encouraged readers to see the lounge for themselves (despite, he acknowledged, his probably being banished for life). Instead of crucifying K-Doe in revenge, the Times scribe made light of a harrowing experience.

Meanwhile, scores of better-behaved musicians searched in vain for their names in print.

When such egregious acts beget such great press, some powerful mitigating forces must be at work. In this case the saving graces were the personal charisma of Ernie K-Doe and the considerable charm of his club. K-Doe, who passed away in 2001, was an adored elder statesman of New Orleans music, a larger-than-life character, and usually an amiable host. The Mother-in-Law Lounge, which thrived in K-Doe’s image until 2010, was a place that filled visitors with giddy wonderment. Their delight ensued from the lounge’s welcoming environment and the surreal sensory overload that walloped all who crossed the threshold. This physical entrance doubled as the conceptual portal into Ernie K-Doe’s eccentric parallel universe—a festive, Fellini-esque realm where shameless idolatry and unfettered happiness reigned supreme. (“There’s a lot of love in here” was a frequent, typical reaction of first-time visitors.)

These intriguing enticements inspired many to bring their friends to the Mother-in-Law Lounge, for the pure fun of watching the newcomers’ enthrallment with this joyous, quirky little bar. The lounge’s hybrid ambience combined elements of a juke joint, a mosh pit, an R&B museum, and a cinematic set from Satyricon. It attracted a similarly eclectic clientele. Well-dressed, middle-aged black people bellied up to the bar alongside white street kids with torn jeans and bizarre piercings. Joining them were politicians seeking cultural credibility, off-duty cops, laborers in dirty work clothes, and fanatical R&B fans on pilgrimages to hallowed music sites around the South. A busload of blue-haired suburban ladies might turn up at any minute, stopping in for a nightcap after a casino gambling excursion. Birthday celebrants might likewise arrive en masse, sporting all manner of outrageous costumes. Derelicts and winos wandered in at times, receiving the same respect as well-heeled customers. The harmonious interactions of these diverse patrons affirmed them in the tradition of Huey P. Long’s credo “Every Man a King.” Or, as Ernie K-Doe often put it, “All you got to do is just keep the faith in what you are doing. You set your goal line, and don’t let nobody change you. You know what you say when people tell you you can’t do something? Fool, shut your mouth up!”

This resolute stance helped propel Ernie K-Doe through years of scuff ling before “Mother-in-Law” hit the top. It also helped sustain him through the long, lean years after his star had faded. He nurtured himself during these tough times with glorious memories of May 1961, when “Mother-in-Law” became the best-selling record in America.

The best-selling record in two Americas, actually—white and black—as delineated by Billboard magazine’s separate sales charts for pop and R&B. “Mother-in-Law” topped both charts, ruling pop’s Hot 100 for a single week and dominating the R&B survey for five.

Compared to these hits and most others of the day, in both pop and R&B, “Mother-in-Law” has very blunt lyrics:

The worst person I know, Mother-in-Law, Mother-in-Law.

She worries me so, Mother-in-Law, Mother-in-Law.

If she leaves us alone, we would have a happy home.

Sent from down below, Mother-in-Law, Mother-in-Law,

Mother-in-Law, Mother-in-Law.Satan should be her name, Mother-in-Law, Mother-in-Law.

To me they’re about the same, Mother-in-Law, Mother-in-Law;

Every time I open my mouth, she steps in, tries to put me out.

How could she stoop so low? Mother-in-Law, Mother-in-Law,

Mother-in-Law, Mother-in-Law.I come home with my pay, Mother-in-Law, Mother-in-Law.

She asks me what I make, Mother-in-Law, Mother-in-Law.

She thinks her advice is a contribution, but if she will leave that will be the solution,

And don’t come back no more, Mother-in-Law, Mother-in-Law,

Mother-in-Law, Mother-in-Law…

Tame as these lines are by contemporary standards, they raised eyebrows in the early ’60s, especially overseas. The English music weekly Melody Maker opined that “Mother-in-Law” “has made a big showing in the States—more, we feel, on account of its simple melodic appeal and rocking beat than the libellous sentiments it contains.” But London’s New Musical Express praised the song as “a cute comedy number in which Ernie tells his mother-in-law a few home truths about herself.”

If K-Doe’s disdainful sentiments in “Mother-in-Law” flirt with libel, his terse and deceptively cool delivery belie its caustic message. In New Orleans speak, this state of obvious annoyance—which, as alert observers realize, could imminently escalate into fireworks—is often telegraphed with the warning “You are working my last single nerve!” K-Doe’s ominously understated, last-single-nerve delivery is complemented by the sparse, less-is-more arrangement of producer Allen Toussaint. Toussaint, a New Orleans rhythm and blues savant who emerged as a major creative figure in American popular music, also plays piano on “Mother-in-Law.” His lilting solo echos the Afro-Caribbean-influenced styles of such seminal New Orleans pianists as Jelly Roll Morton (Ferdinand LaMothe) and Professor Longhair (Henry Roeland Byrd). A century before “Mother-in-Law,” the same folk traditions had inspired the classical compositions of native son Louis Moreau Gottschalk.

“Mother-in-Law” was so popular that it inspired two “answer songs”: “Son-in-Law,” by the girl group the Blossoms, also recorded by Louise Brown (“the other day he even hocked her wedding ring”), and “Brother-in-Law (He’s a Moocher),” by rockabilly artist Paul Peek (“He’s lazy, won’t work, never had a job—get out of my house, you big fat slob”). “Mother-in-Law” is still considered a classic of overlapping genres, including R&B, pop, rock, and the loosely defined “beach music” of the Carolina coast. It has been reissued on at least a hundred anthologies and continues to get significant airplay on such diverse programs as Theme Time Radio Hour with Your Host Bob Dylan and American Routes with Nick Spitzer, and numerous oldies shows on R&B and pop stations. A multitude of new renditions continue to be recorded, including several Spanish-language versions, commonly titled “La Suegra.” In New Orleans, where the borders between musical genres are extremely porous, bands of every sort are asked to play “Mother-in-Law.” They’re expected to know it, along with K-Doe’s regional hits “T’aint It the Truth,” “Hello My Lover,” “Te Ta Te Ta Ta,” and “A Certain Girl.” None of these other fine songs achieved national success comparable to that of “Mother-in-Law,” but all are perpetual Gulf Coast favorites. Collectively they established the reputations of Ernie K-Doe and Allen Toussaint as masters of New Orleans rhythm and blues.

This was no small achievement at a time when that field was quite crowded. A vast surge of creativity and commercial success energized the Crescent City from the late 1940s to the early ’60s, an era later dubbed the golden age of New Orleans rhythm and blues. A cursory list of its other luminaries includes Fats Domino, Professor Longhair, Shirley and Lee, Smiley Lewis, Irma Thomas, Lee Dorsey, Lloyd Price, Art Neville, Aaron Neville, Huey “Piano” Smith, Frankie Ford, and Clarence “Frogman” Henry. The Meters and Dr. John, who emerged in the late ’60s, and the Neville Brothers (with siblings Aaron, Art, Charles, and Cyril), who formed a decade later, also stand in that illustrious number. So do the musicians who accompanied these artists on many of their records: saxophonists Lee Allen and Nat Perrilliat, drummers Earl Palmer and Smokey Johnson, bassists Frank Fields and Lloyd Lambert, and guitarists Roy Montrell, Justin Adams, and “Deacon” John Moore, to name but a few.

Ernie K-Doe felt thrilled when “Mother-in-Law” reached the top. He felt gratified decades later by its staying power. But he never ever felt surprised. “There ain’t but two songs that will stand the test of time,” K-Doe often declared. He would then pause at considerable dramatic length before naming them: “The first song is ‘The Star Spangled Banner,’ and the second song is ‘Mother-in-Law.’ Because people gonna have a mother-in-law until the end of the world.”

If K-Doe exaggerated his song’s importance, he did not overstate its broad, perpetual appeal. Negative depictions of mothers-in-law date back at least to the Roman satirist Juvenal: “Give up all hope of peace so long as your mother-in-law is alive.” Countless comedians, Henny Youngman for one, have echoed Juvenal’s sentiments: “I bought my mother-in-law a chair. Now they won’t let me plug it in.” And men are not alone in alleging persecution. The website www.motherinlawhell.com was created for “the daughterin-law sisterhood . . . you are not alone. stop suffering in silence.” In an article entitled “Women’s Studies and Popular Music Stereotypes,” B. Lee Cooper mentioned K-Doe’s hit while proposing that “ideas about hateful maternal relatives . . . need to be tempered.”

But such mellowing entails an arduous slog through dense cultural attitudes. Emotional issues factor in, too, including the fear of dominant personalities.

Ernie K-Doe did not fear his mother-in-law. Au contraire, he bragged about throwing her out: “My first wife’s mother’s name was Lucy—but it should have been Lucifer! . . . She used to wake up six o’clock in the morning to bring me daytime nightmares. . . . She was staying at my house, eating up all my grub and talking her noise. I took her outside in the pouring rain. I said, ‘You know something—when a boil comes to a head, you ain’t got to squeeze it, it busts itself, and you done busted that boil now. I want you out of my house!’ I told her, ‘This street run to the left, and this street run to the right—NOW PICK ONE!’ I walked back inside and my first wife said, ‘Where Mama?’ I said, ‘Come look out the window—I can show you better than I can tell you!’”

This is an excerpt from ‘ERNIE K-DOE: THE R&B EMPEROR OF NEW ORLEANS’ by Ben Sandmel. Copyright © 2012 by Sandmel Enterprises LLC. Reprinted by permission of The Historic New Orleans Collection. All rights reserved.